Towards 1.5-degree lifestyles

The urgency of the climate crisis has highlighted the need to reduce our personal carbon footprints. Sometimes the discussion feels very polarised, like there was only one “sustainable lifestyle” and everyone should fit the same mould.

The IPCC report in 2018 gave urgency to the climate debate: staying within the 1.5-degree target for global warming is still possible but requires action within the next decade. The scale of the action was quantified in the study 1.5-Degree Lifestyles by Aalto University and Sitra. The study pointed out that the 1.5-degree target means that within just 11 years, by 2030, the carbon footprint of the average Finnish lifestyle needs to decrease from the current 10 tCO2e (later tonnes) to 2.5 tonnes. Furthermore, the study points out that our carbon footprints in 2050 should be only 0.7 tonnes per person per year to hit the IPCC target.

In this article, we present four alternative lifestyles that will help meet the 2030 targets. We looked at what the transition will mean for the life of four different fictional characters with very different lifestyles (and their subsequent carbon footprints), values and motivations. This is by no means is an extensive mapping of potential lifestyles, as there are as many lifestyles as there are people.

The pathways consist of changes in individual, civic and political actions, as well as in consumer choices and technologies. The changes portrayed are not only motivated by climate consciousness but occur as an organic part of the lives the people live: they grow up, move to a new apartment or start a new hobby and so forth. Given the right conditions, these moments of change can also take a sustainable path. This, however, cannot happen without enabling policies and the availability of low-carbon commercial choices, that suit each lifestyle, becoming the default options. We call these limiting factors as the key enablers.

Many of the technologies that can provide this new default already exist. They must, however, be scaled up, mainstreamed and commercialised at such speed that it requires an urgent push from governments and investment from industry. Thus, this report offers recommendations for policymakers and highlights the areas for business opportunity that will emerge from the change in policy and lifestyles.

To enable systemic change and to escape the solely individualist point of view that often distorts low-carbon lifestyle studies, we describe here the carbon handprint people may have. By carbon handprint we mean positive actions that extend beyond one’s own lifestyle, actions that help other people or the whole of society to reach the 1.5-degree target. These include consumer, civic and political activities, such as the choices people make at school, at work, while practising hobbies, while shopping, online and on the street.

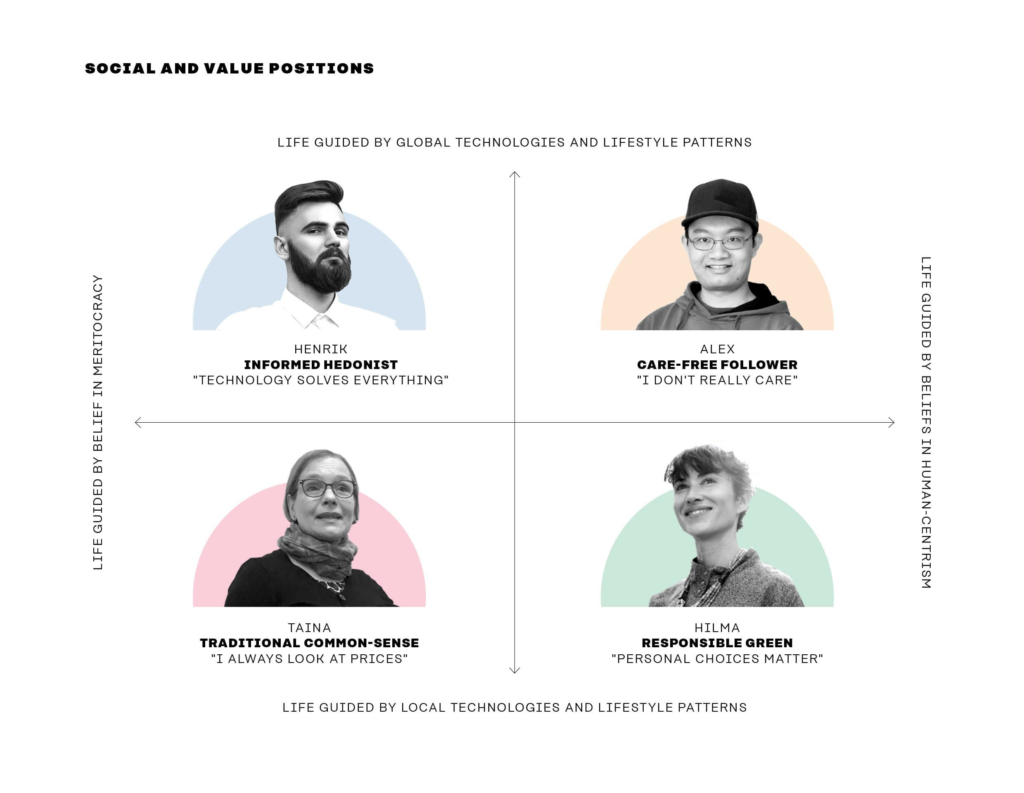

Meet the people: four characters with different lifestyles and values

To illustrate what the transition to low-carbon lifestyles might look like, we would like to introduce four people with different lifestyles, values and motivations. These people represent different types of people living in the Nordic countries. The attributes of these people are based on previous work featured in the SPREAD Scenarios for Sustainable Lifestyles 2050 and the Motivation profiles of smart consumption.

Henrik, 40, the “informed hedonist”, is a well-educated tech enthusiastic with an active lifestyle who lives in a wealthy neighbourhood in Helsinki. Although he is aware of environmental issues, he still consumes a lot. He believes that technology can solve the climate crisis.

Taina, 65, the “the pragmatic traditionalist”, is a soon-to-retire geriatric nurse with a strong connection to her local community. She lives in a small town. She practises things that she believes are reasonable with common sense. Economic welfare is important to her. She always compares prices before making decisions.

Hilma, 32, the “responsible green”, is an active association member with a thrifty and (thus) green lifestyle, who initially lives alone in a studio apartment in a medium-sized city. She believes that consumer choices can make a difference. Of all the four, she is the most environmentally aware and ecological consumer, although mostly for economic reasons.

Alex, 16, the “care-free follower”, is a teenager looking for his own path to follow, living in a suburban area with his mother. He does not consider the environment in his actions but follows the example of the people he admires.

The figure below illustrates the different social and value positions of the four people. Please also find the more detailed graphs here: Pathways to 1.5 degree lifestyles: detailed table charts

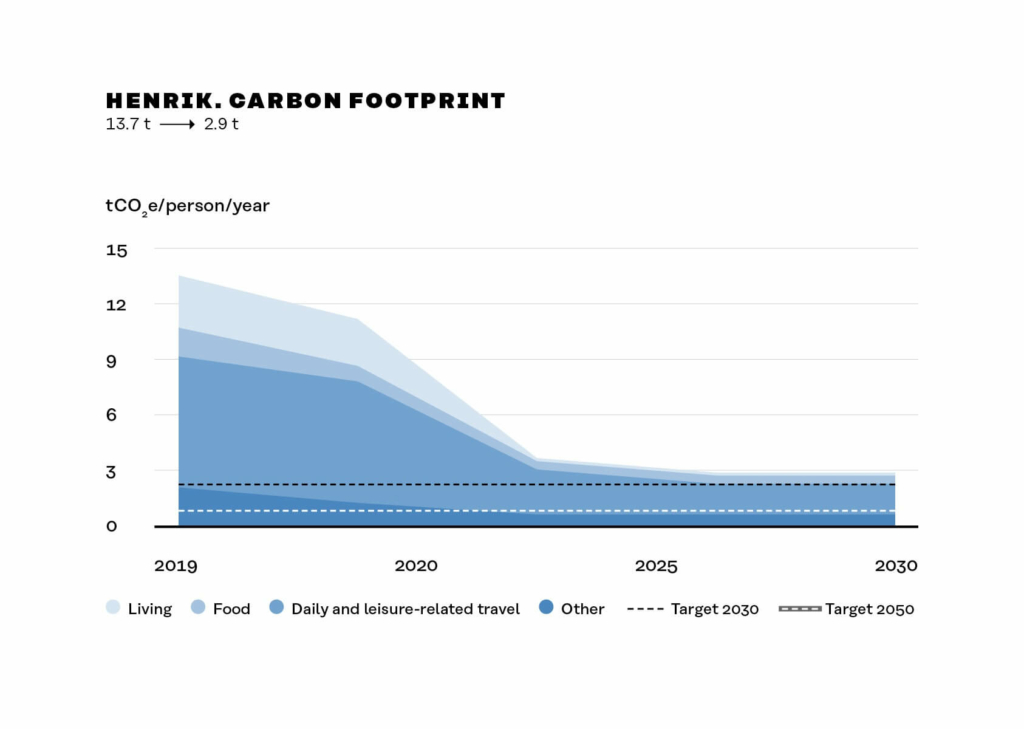

Henrik – Informed hedonist with a wealthy and active lifestyle

Henrik is a 40-year-old IT consultant living in a big city with his spouse and two children. He is a social and active person who loves sport and the outdoors and spending time with family and friends. Being trendy is important to him and he embraces changes that improve the quality of his life. As a tech enthusiastic he especially likes to try new innovations, from apps to machines. He consumes a lot, with a carbon footprint of 13.7 tonnes, but is aware of environmental issues and thinks that problems like climate change can be solved through technology.

Consumer profile: Henrik makes choices according to style and identity, and embraces individualism, good quality and good vibes. He wants to do things right and is willing to adapt an ecological lifestyle, although he is not willing to compromise on quality. Despite wanting to serve as an example to others, Henrik craves pleasure and luxury.

Statistics: Henrik is typical of the highly qualified professionals that live in large cities. In 2017, 31% of the Finnish population had completed a tertiary-level qualification, and 36% lived in blocks of flats. In the same year, there were 566,242 families with children in Finland, and 29% of all households used district heating.

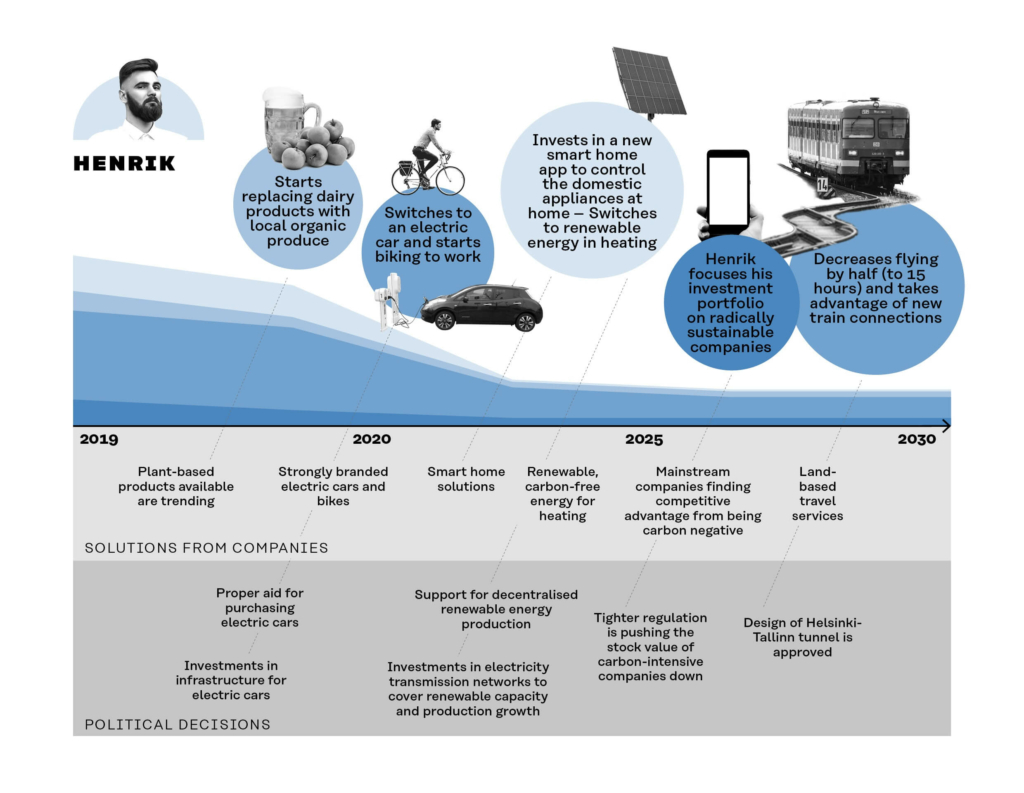

Henrik’s pathway by 2030

Food

Henrik starts buying home-delivered, organic, locally produced food from online grocery stores and the marketplace nearby, as he finds it trendy and healthy. He starts favouring local fish and replaces dairy products with plant-based alternatives. Changes in eating habits allow him to lower his nutrition-related carbon footprint from 1.6 tonnes to 0.5 tonnes.

Daily and leisure travel

As an active and trendy person, he starts to go to work by bike. He also switches to an electric car, which he has dreamed of ever since he first learned about Elon Musk. He decides to take a longer vacation with his family and chooses to use the efficient network of high-speed trains, as flying now has a poor image in the media and within his circle of acquaintances. These changes reduce his travel-related carbon footprint from 7.1 tonnes to 1.7 tonnes.

Living

To coincide with the housing co-operative carrying out an energy renovation of his apartment building, Henrik invests in a new smart home app to control his domestic appliances. For instance, the app helps to monitor and lower the room temperatures. A local heating provider starts marketing new renewable heat energy extensively, and Henrik wants to be among the first to embrace it. He starts buying renewable district heating. He is really proud of his decision and remembers to mention it to all his neighbours and colleagues. As a result, Henrik’s living-related carbon footprint is reduced from 2.8 tonnes to 0.2 tonnes.

Other

Henrik’s apartment starts feeling cramped as his children grow up fast. Since living in a neat and tidy place is important to Henrik, he gets excited about a new online service where stuff like old clothes, sports equipment and furniture are picked up, repaired and sold on. As he sells his old stuff, he refrains from buying replacements. His carbon footprint generated by his miscellaneous consumption habits reduces from 2.1 tonnes to 0.7 tonnes.

Key enablers

Henrik’s choices are mostly influenced by trends and opportunities to improve the quality of life. His children have more and more impact on his decisions as they grow up: the younger generation these days is learning about the basics of sustainable lifestyles at school.

Carbon handprint

Henrik’s carbon handprint is visible both locally and globally. He organises an energy renovation for the whole apartment building he lives in. After being elected to the city council, he pushes carbon-neutral solutions for the city. Partly through carbon compensation, he also becomes interested in sustainable investments and starts to invest in renewable energy in developing countries.

Taina – A traditional “common-sense” person with a strong connection to her local community

Taina is a soon-to-retire geriatric nurse living in a small town with her spouse. She has lived all her life in the same town and knows basically everyone. Locality is important to her and she likes to support local companies if financially reasonable. She likes to spend time at home and go to the family summer cottage and local events during the summer. Her carbon footprint is a bit lower than the average Finn, 9.9 tonnes per year.

Consumer profice: Taina practises things that she believes are reasonable: she buys mostly useful products that can be fixed, prefers to save money and trusts traditional domestic manufacturers and suppliers. Her consumption habits are smart and sustainable, inspired by economic and practical concerns. However, environmentalism and new technological solutions are something that she is unfamiliar with and suspicious of.

Statistics: Taina is typical of the population of small towns that live in large detached houses. In 2017, around one half of Finns lived in detached houses and 34% used electric heating. In the same year, around one third of households consisted of two people, and in 2019 there were 695,000 people in her age group (65-74).

Taina’s pathway by 2030

Food

Taina becomes more aware of her own health and cuts down on sugar, coffee, meat and dairy products. As the healthier stuff is slightly more expensive, and waste disposal fees have increased, she makes sure that she doesn’t throw food away, and starts buying discounted food that would otherwise be thrown away. These changes reduce Taina’s food-related carbon footprint from 3 tonnes to 1.1 tonnes.

Daily and leisure travel

The government levies increased taxes on fossil fuels that drives Taina to switch to biogas. She finds it rather easy, as adding gas tanks to cars is already supported by the government. Convinced by her son, she occasionally starts loaning out her car to a car-share scheme to earn some extra money. When her son moves to Brussels, she finds out that plane tickets have become far more expensive than they used to be. Fortunately, she can make the visit by train with an all-inclusive train and boat travel package. With these changes, Taina’s travel-related carbon footprint reduces from 2.4 tonnes to 0.7 tonnes.

Living

Taina’s neighbour suggests that the whole neighbourhood should install geothermal heating, since the investment pays off and is supported by low-cost financing. Taina agrees, as staying on good terms with her neighbours is important to her. She decides to lower the temperature at home and install solar panels at her summer cottage to save some more money as well. These changes reduce her living-related carbon footprint from 3.6 tonnes to 1.2 tonnes.

Other

Shocked by the price of new sports gear, Taina enters the world of online second-hand shopping. It isn’t as difficult as she thought, and soon most of her shopping lands on her doorstep without her having to move a muscle. She recycles more, and even buys a used electric bicycle. The carbon footprint generated by her other miscellaneous consumption habits of 0.9 tonnes reduces to 0.4 tonnes.

Key enablers

As Taina is unlikely to become proactive in “going green” by herself, external incentives and influences are essential. Her own children in particular can play an important role, as their generation is more attached to global trends and new sustainable practices at work and in places of study.

Carbon handprint

After receiving good experience on geothermal heating and solar power, Taina starts to recommend them to her local community, also as a source of income. She encourages her friends to switch into biogas cars as the operation was really easy. Taina supports the local economy by buying and promoting local products.

Hilma– An active association member with a thrifty and (thus) green lifestyle

Hilma loves reading and has been working as a librarian after graduating from university a couple of years ago. She lives in a medium-sized city, likes the outdoors and travels by bike when possible. In her free time, she participates in association activities. She also likes to use her housing co-operative’s shared sauna and go to their events. Hilma is an aware, ecological consumer with a carbon footprint of 6.6 tonnes, which is a result of being thrifty.

Consumer profile: Hilma seeks to reduce everything: consumption, waste and injustice in the world. She always takes nature and the environment into consideration and is willing to cut down on comfort to live sustainably. She sympathises with local producers and buys only good-quality products that are made according to her values. Despite being a responsible consumer, Hilma’s sceptical attitude towards new trends and consumerism may prevent her from adapting new eco-friendly products and services.

Statistics: Hilma’s living conditions are typical of the young adult population living in single-person households. In 2017, there were over 1.1 million single-person households in Finland, which is almost one half of all the households in the country. In the same year, 36% of the population lived in blocks of flats. In 2019, there were 706,000 people within her age group (25-34).

Hilma’s pathway by 2030

Food

As plant-based alternatives to meat and dairy products become relatively cheaper, Hilma switches to them altogether. She joins a local food co-operative and starts to buy and use organic and self-produced vegetables between June and September. The decision is economical, but even more social: Hilma meets other people who are interested in supporting local food production and enjoys the feeling of community. Her food-related carbon footprint is reduced from 1 tonne to 0.4 tonnes.

Daily and leisure travel

Hilma decides that she has flown her last flight (flying has become more expensive and she suffers from climate anxiety, too) and starts to use the new night train between Oulu and Stockholm. She buys an electric bike and starts to cycle all-year-round. She works remotely part of the time and takes more days off, which decreases her travel to her workplace. She highly values the increased amount of free time and uses it for hobbies, helping in the neighbourhood and planning a housing co-operative project. These changes reduce her travel-related carbon footprint from 1.9 tonnes to 0.4 tonnes.

Living

Hilma starts a housing co-operative with her five friends and renovates an old wooden house to a high standard of energy efficiency. The co-operative produces most of the electricity with the solar panels on the roof and sells the spare electricity to the grid. Hilma also keeps the room temperature low and washes dishes less frequently. Her flatmates feel like a family to her – they include singles, couples and kids. The changes in living allow her to lower the living-related carbon footprint from 2.6 tonnes to 0.7 tonnes.

Other

Hilma avoids buying any new products and buys as many recycled products as possible. She starts a social media group for her neighbourhood that allows the sharing of appliances and tools more easily, and she takes more days off work. These and other small changes in her lifestyle allow her to reduce her miscellaneous consumption-related carbon footprint from 1.2 tonnes to 0.5 tonnes.

Key enablers

Hilma’s choices are mostly affected by her like-minded friends and the local community which aspires to live a thrifty and ecological life. Her employer enables the reduced working time and provides space for the communities outside official opening hours.

Carbon handprint

Hilma sets an example to many other people with her personal choices. As part of her work at the library, she arranges for different equipment and tools to be loaned out. She always votes for climate-friendly candidates, and she sponsors a child in Bangladesh. She also encourages and helps her parents to switch to green energy. In addition, her voluntary work for many NGOs leaves a carbon handprint as well.

Alex – A teenager drifting along before finding his own path

Alex is a 16-year-old teenager studying in upper secondary school. He lives with his mum in a suburban town and, as his parents are divorced, he visits his dad every second weekend. Alex spends a lot of time online chatting with friends and playing video games. He doesn’t want to stand out from the crowd but would rather follow what others do. His carbon footprint is just below the Finnish average, being 9.2 tonnes.

Consumer profile: Alex gets motivated by the people he admires and phenomena that go viral. He does not consider sustainability or the environment, as the societal issues are distant and not interesting, although he is willing to make smart choices if they are easy and affordable enough. He buys things “just for fun” and follows the example of his friends and other close people. While prioritising his own comfort, happiness and benefits over solving environmental or societal problems, Alex is also very restricted in a financial sense.

Statistics: Alex is typical of upper secondary school-aged suburban teenagers who are about to embark on an independent adult life. There were 616,000 people in his age group (15-24) in 2019, and there were around 100,000 upper secondary school students in 2017. In the same year, 13% of the population lived in townhouses (source: Statistics Finland).

Alex’s pathway by 2030

Food

As Alex’s school starts serving mostly plant-based food, he gets used to these alternatives – there is no great difference compared to the meat products. His family starts eating plant-based food too, as supply and demand increase and social pressure grows. Regulations and his parents’ choices play an important role in these changes in eating habits, which decrease his food-related carbon footprint from 1.6 tonnes to 0.9 tonnes.

Daily and leisure travel

MaaS (mobility as a service) services cover the whole country and have become tailored to students and other population groups, which means that Alex does not need to buy his own car. As greater regulation has increased the price of air travel, he spends the summers inter-railing instead of flying. Economic and practical reasons are also central to his choices of travel. These changes decrease his travel-related carbon footprint from 2.6 tonnes to 0.3 tonnes.

Living

Alex moves into affordable energy-efficient wooden student housing. As single apartments have become very expensive, all the cool kids live in these dorms now – trends have shifted towards communal student living. Changes in living allow Alex to lower his living-related carbon footprint from 3.5 tonnes to 0.6 tonnes.

Other

Alex doesn’t like shopping but is jealous of the cool new clothes his friends are wearing almost every week. He hears that the clothes were rented through an online clothing rental service and decides to try it as well. By changing mainly to rental clothes and repairing his own beloved items, Alex can reduce his miscellaneous consumption-related carbon footprint from 1.5 tonnes to 0.7 tonnes.

Key enablers

Alex’s decisions are mostly affected by his friends, trends and regulation. His actions are dictated by his parents’ and school’s climate actions while he lives at home. As he starts living independently, there is greater opportunity for him to start making his own sustainable choices.

Carbon handprint

At school, Alex participates in sustainable development projects that bring joy to the whole neighbourhood. At university, he also takes part in a course where the emissions and ethics of technology are studied together with a partner university in Africa.

Main messages

1. The 1.5-degree targets are still attainable.

All the example people in our report were able to significantly reduce their carbon footprints by 2030. It is possible with very different lifestyles and motivations if the change is enabled in the right way.

2. Let’s not argue anymore about who should solve the crisis – the targets can be reached if we all act now.

Taina, Alex, Henrik and Hilma all need different support, different products and different means of communication, seeing as their values and motivations are each so different. What is common to them all is that they all need to feel that any transition is fair. What are needed are zero-carbon products and services that make our lives better than before.

Most of the enabling technologies and options for 2030 already exist but are not yet considered mainstream. It is crucial to remove the barriers and support the scaling of these technologies and options immediately in order to make the lifestyle changes happen. The role of business is crucial, because this also represents a major business opportunity.

3. Compensation is important but first we have to reduce footprints as much as possible.

There are still some major concerns and questions related to compensation for the carbon emissions that form our footprint. It is an important part of solving the climate crisis but should not be used as an excuse to continue high-footprint lifestyles.

4. Let’s start envisioning 1.5-degree societies in 2050

The pathways to 2030 and the associated 2.5-tonne target are relatively easy to identify, because the enabling technologies and policies already exist. Envisioning welfare societies in 2050, where carbon footprints amount to less a tonne, is still challenging. Systemic changes are not achieved in a short time, but the decisions we make now should enable and not prevent us from facilitating long-term systemic change.

Final note: we didn’t include everything in these profiles…

In order to simplify the timelines, we have not included estimates for smaller but no less important aspects such as education, work, hobbies and voluntary organisations. But they too can play a major role in achieving the 2030 targets.

How the profiles were created

The footprint calculations for the four examples are based on Sitra’s Lifestyle Test. A detailed description of the calculation basis used in the test can be found in the Lifestyle Test’s background material (Toivio and Lettenmeier 2018).

The scenarios are based on an interactive tool, the “1.5-degree lifestyle puzzle”, which was developed as a part of the “1.5-degree lifestyles” project (Institute for Global Environmental Strategies et al. 2019; Lettenmeier et al. 2019). The puzzle pieces are based on Sitra’s list of 100 smart ways to live more sustainably but are modified to fit the average Finn’s carbon footprint. A more detailed description of the interactive tool is described in Lettenmeier et al. 2019.

Interviewed experts

The personas and pathways were further developed in an expert workshop and through interviews in May 2019.

Scenarios and pathways to 1.5-degree lifestyles 2030 and 2050 workshop (Helsinki, 13 May 2019)

List of expert participants

Maija Aho, Huhtamäki

Saara Azbel, Marimekko

Senja Forsman, SOK

Juha Honkatukia, National Institute for Health and Welfare

Angelina Korsunova, Aalto University

Satu Kuoppamäki, OP

Michael Lettenmeier, D-mat

Lassi Linnanen, LUT University

Sonja Nielsen, D-mat

Anniina Nurmi, Vihreät vaatteet

Tina Nyfors, LUT University

Eeva Salmenpohja, Kesko

Osmo Soininvaara

Saana Tikkanen, Palmu

Viivi Toivio, D-mat

List of participating project partners and advisors

Sanna Autere, Sitra

Yuri Birjulin, Demos Helsinki

Emma Hietaniemi, Sitra

Sari Laine, Sitra

Tyyra Linko, Demos Helsinki

Roope Mokka, Demos Helsinki

Markus Terho, Sitra

Oona Tiainen, Sitra

Lotta Toivonen, Sitra

Additional interviews

Saara Jääskeläinen, Ministry of Transport and Communications

Mariko Landström, Sitra

Mikko Viljakainen, Puuinfo

References

Demos Helsinki, 2012. SPREAD Scenarios for Sustainable Lifestyles 2050: From Global Champions to Local Loops. D4.1. Future Scenarios for New European Social Models with Visualisations.

Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Aalto University and D-mat Ltd, 2019. 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Targets and Options for Reducing Lifestyle Carbon Footprints. Technical Report. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Hayama, Japan.

IPCC, 2018: Global warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty.

Lettenmeier, M., Akenji, L., Toivio, V., Koide, R. and Ammellina, A. 2019: 1.5 asteen elämäntavat. Miten voimme pienentää hiilijalanjälkemme ilmastotavoitteiden mukaiseksi? Sitran selvityksiä 148.

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Dwellings and housing conditions [e-publication]. ISSN=1798-6761. 2017, Appendix table 1. Household-dwelling units by number of person 1960-2017 . Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 29.5.2019].

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Dwellings and housing conditions [e-publication]. ISSN=1798-6761. Overview 2017, 2. Household-dwelling units and housing conditions 2017 . Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 29.5.2019].

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Educational structure of population [e-publication]. ISSN=2242-2919. 2017. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 29.5.2019].

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Energy consumption in households [e-publication]. ISSN=2323-329X. 2017, Appendix figure 1. Energy consumption in households by energy source in 2017. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 29.5.2019].

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Families [e-publication]. ISSN=1798-3231. Annual Review 2017, Appendix table 5. Families with underage children by language of parents on December 31, 2017 . Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 29.5.2019].

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Labour force survey [e-publication]. ISSN=1798-7857. March 2019, Appendix table 3. Population by sex and age 2018/03 – 2019/03 . Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 29.5.2019].

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Upper secondary general school education [e-publication]. ISSN=1799-165X. 2017. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 29.5.2019].

Griscom, B. W. et al.: Natural climate solutions. Forests and ecosystems as carbon sinks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11645–11650 (2017)

Sitra and Palmu, 2018: Fiksu kuluttaminen Suomessa. Motivaatioprofiilit apuna liiketoiminnan kehittämisessä. Sitra, Helsinki, Finland.

Toivio, Viivi and Lettenmeier, Michael 2018: Calculation basis used in the Sitra lifestyle test. Update 22.8.2019.