Ask urbanites to describe who lives on the wrong side of the digital divide, and you’ll likely hear an answer that involves some combination of people who are poor, live in rural areas, and lack education.

That assessment isn’t wrong, but it isn’t complete, either. Across eight major economies—among them the US, India, China, and Japan—24 percent of city dwellers are not connected to the Internet.

The digital divide runs through big cities and small towns, keeping billions of people from a vital source of information, knowledge, and economic opportunity.

The cost is substantial. People without reliable Internet access have a more difficult time finding jobs, developing new skills, and improving their economic status, according to a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

A look at one European economy exposes the roots of the problem and shows what can be done to address it.

Examining Italy’s Digital Divide

In some ways, Italy is a paradigm of the world economy—a country undergoing a long-term shift from agrarian society to knowledge economy. That shift has driven much of the population to cities, creating an urbanization phenomenon common in developed nations. Today, just 30 percent of Italy’s residents live in rural areas. As recently as 1960, 66 percent did.

Across the country, 6 in 10 Italians are connected to the Internet—a fairly low rate for a developed economy. (By comparison, America’s rate is 76 percent; Japan’s is 91 percent, and the UK’s is 95 percent.)

In part, Italy’s digital divide is the byproduct of geographic and economic barriers that few Internet service providers are willing or able to overcome. In the country’s mountains, hills, and valleys, it is not economical to install the fiber wiring that could deliver a broadband digital connection to each house.

Yet, where other companies saw small clusters of residents and a bevy of technical challenges, one Internet service provider saw a business opportunity mixed with a social good. The company used location intelligence to peer through the barriers that kept other providers out of the market.

Seeing Unseen Opportunities

“It’s easy to cover a big city with fiber,” says Daniela Daverio, CFO of Italian Internet service provider EOLO. “It’s very difficult to cover the municipalities in Italy. But we know that the people are in little cities. So for a social goal, it’s important to have a solution.”

EOLO’s solution is to provide Internet access via a wireless connection. Beginning in 1996 in the north of the country, the company began placing base stations—often in mountainous regions—that beamed broadband access to homes within the station’s line of sight. This over-the-air service doesn’t match the fastest wired Internet speeds (it maxes out around 100 MB per second), but it enables video streaming and other services expected of a modern connection.

EOLO’s customers number 400,000. A quarter of them signed up last year and 150,000 more are expected to this year. Collectively, they are a testament to the equalizing force and economic power of the Internet. They include:

- Husband-and-wife vintners who sell their wine on the Internet

- The 32 inhabitants of Italy’s smallest town, who are now connected to public Wi-Fi and electric vehicle charging stations

- The operator of a chalet in the Alps—five days by foot from the nearest supermarket—that takes online reservations for lunch and dinner

- A rural flight instructor who stores important customer data in the cloud

But as Daverio suggests, bridging the digital divide to reach these customers was no small feat. EOLO executives did it by using technology that helped them see what others couldn’t.

KPIs Illuminate Smart Maps

EOLO’s highest concentration of customers live in northern Italy, but over the last decade the company has expanded its service to the country’s midsection. Just this spring, it activated base stations in southern Italy, bringing service to Campania, Sardinia, and Sicily.

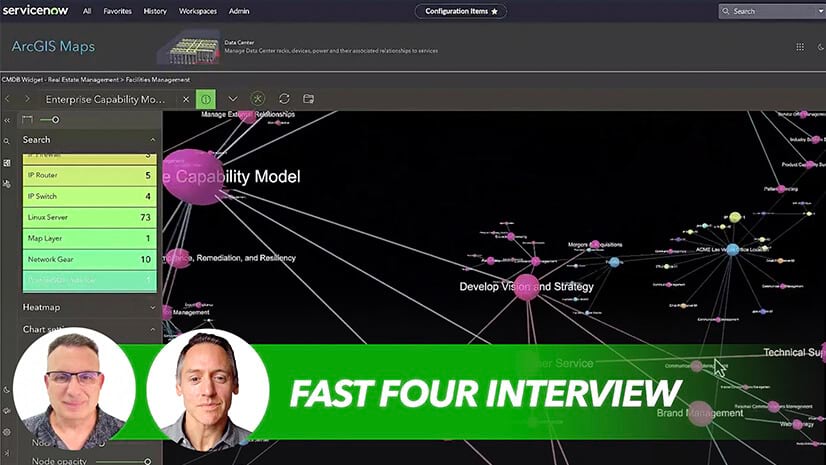

Each town EOLO adds to its territory represents a major capital investment, and executives make those decisions with the help of smart maps. Powering each map is a modern geographic information system (GIS) that helps executives clearly see the technical and business challenges before them.

“In strategic planning, it’s very important to know how to invest in a territory to have a return on investment,” Daverio told WhereNext. “We use GIS to know the promising territory, to know the growth of the possible customers in this territory, and so I can do a profit and loss for each area. It is very easy to make strategic decisions with the KPIs that I have.”

Those KPIs on investments and network performance appear as layers on the smart map created by Riccardo Armellini and his colleagues—members of EOLO’s strategic planning team. GIS, he says, has given decision-makers clearer vision.

“I think they can see things that they didn’t see before,” Armellini says. “It’s another point of view to drive better decisions.”

The first data layer Daverio and her colleagues review shows how many potential customers a town or small city holds. That data comes directly from the company’s website, where residents enter their addresses to see whether EOLO provides service to their area. Those requests show up as clusters of dots on the smart map.

Armellini and the GIS team deepen the analysis by layering in additional levels of location intelligence, including demographic data on how many families live in the area and how many businesses operate there. That insight helps round out the demand picture, revealing whether there is enough interest to make EOLO’s investment profitable.

But the market assessment isn’t complete until the engineers weigh in.

With GIS, we can see all the KPIs that are important to knowing the business and to knowing the trend of [customer] orders. It's important to do this analysis.”

Taking the Measure of the Land

The critical next step for EOLO is a suitability analysis that determines whether the company’s wireless service will work in the prospective location.

Consider an Italian town of a thousand people. The GIS-powered smart map shows a healthy percentage of inhabitants interested in broadband service. Now, EOLO engineers must decide where to place a base station to ensure line of sight to as many homes as possible.

They use GIS to analyze the town’s morphological data—the exact slope, undulation, and elevation of the land relative to the position of houses. In that way, GIS helps technical planners design a coverage map that pinpoints which buildings can receive Internet service.

But it’s not purely a technical undertaking—it’s also a business exercise that affects ROI.

“We are showing the technical division some commercial bits of information,” Armellini says. “If [the engineers] know exactly where the potential is, they can design the base stations and the coverage for exactly the right area.”

Location intelligence helps us to be more efficient in our development, to develop our network in the right places, and to cover the right areas and expand our market.

Seeing KPIs to Propel the Business

As towns and small cities come online, EOLO executives monitor their status through the smart map, assessing KPIs such as service activations, customer churn rates, and market share, as well as network quality and congestion.

“It’s very easy to use [the map] because you can turn on a single KPI or turn off different KPIs at the same time,” Daverio says. That form of location intelligence helps decisions-makers see the status of EOLO’s networks, as well as the company’s market opportunities.

“Without GIS, it would be like throwing dice,” Armellini says. “You don’t know where to go, and why to go there.”

Speaking of location intelligence technology, Daverio says, “I think that the most important thing is to use this tool to go directly to the correct area, the correct investments. For example, in the south of Italy, I see all these logs. I know that is a territory where we can do very good with our solutions.”

For EOLO customers Simone and Miriam, winemakers in the north of Italy, the fruits of crossing the digital divide are clear. The Internet, they say, has opened new markets for them. They now sell 10,000 bottles of wine online, and live-broadcast the grape harvest on Facebook.

It’s a story that mirror’s EOLO’s own. With the guidance of smart maps, EOLO has found new markets in overlooked places, bringing more citizens across the digital divide.

(For an inside look at how India’s largest mobile network operator built the infrastructure to serve 350 million customers, read this Esri Blog.)