For over six months, a background application tracked every use I made of my Sony CLIE SJ-22 PDA (PalmOS 4.1, grayscale 320×320 resolution, 16MB internal & 128MB expansion memory). I do not represent an average user, but rather an enthusiast user who tried as broad a spectrum of programs as possible. The PDA was accessible (in pocket) at almost all times every day, was hotsynced daily, and internal and external memory was always kept within 10% of capacity. Like any good enthusiast, I used a lot of third party (enhanced from the default) applications.

Study Results

Overall number of uses: 9539. Overall time of uses: 173 hours. All numbers in the table are estimates. Table ordering is retained in the histograms.

The combined calendar and address book program was used most frequently–it accounted for 43% of total uses and 25% of the total time. It is a good sign a program (or programs) that performs these functions ships standard on all PDAs.

Overall, functions that were performed by programs that shipped with this PDA (address book, calendar, memo pad, calculator, to do list, email) accounted for 64% of the total uses and 35% of total time. Even though this is a large amount of use, this still leaves the majority of time and a very significant percentage of uses in the hands of third-party developers–and distributed across a lot of programs. There is obviously a lot of use that PDA manufacturers do not make available by default to users. The use analysis still leaves important questions about PDA usage unanswered: Are there advantages of PDAs that most users are missing? Are these advantages usable by non-enthusiast users? If so, could PDA manufacturers take advantage of these to make their products more useful (and desirable) to users? The following section addresses some of these issues by categorizing and explaining types of use.

Notes:

A major application was not included in this analysis is the English-language dictionary (it was not recorded by the use logger). This is only a guess, but I think that I probably spent at least as many uses on it as I did on the memopad. The hotsync application, though logged, was not included in the analysis because it reflects computer interface time–not human use.

How can PDA uses be categorized? Can these uses be performed in a paper-based format?

Because analysis of usage data alone cannot give the reason why programs are useful, I categorized PDA programs into three categories based upon the cognitive advantage they offer to users. Besides a cognitive and physical justification for these categories, I analyzed the possible cognitive advantages PDAs have over traditional paper alternatives in these areas:

1) Offloading long-term and short-term memory

Long-term memory is aided by programs (e.g. datebook, address book, memopad) that provide representations of thoughts that are normally expected to be committed to either internal human memory or an external memory agent (like paper). This represents the bulk of my PDA use, and these are the programs that are most likely to be included by default on PDAs. This can also be accomplished well with paper, though it might involve a somewhat hefty planner/organizer.

Short-term memory is aided by programs that provide representations of things that people normally have to commit to human memory. My favorite is Diddlebug–an elegant and simple open-source program. It allows the user to scribble on the PDA screen and then set an alarm to sound after a prescribed time period. The scribble can be anything from text to a picture–thus, any visual short-term memory can be offloaded and forgotten about. When the time comes to remember, the PDA beeps and the scribble is displayed. Certainly, paper cannot function as a time-based reminder–unless that paper is associated with something that keeps track of time.

2) Enabling the use of massive amounts of data

Programs (e.g. Hypertext references, books, newspapers, medical references) can enable users to reference or query large databases of information. Most of my references involved task-specific encyclopedia or dictionary material (e.g. “Who was in that movie?,” “How old is that person?,” or “What is that word in Spanish?”), but there were some non-task-oriented data references as well (books, newspapers). Though massive reference material can be referenced via paper-based tomes, these are being displaced by searchable electronic formats. This advantage is not being exploited as well as it could be most PDA users and even simple dictionaries are not included by default on PDAs.

3) Enabling the use of complex interactive reference tools

Programs (e.g. calculators, unit converters, electronics and astronomical references) can enable users to make use of interactive reference tools. While some (not all) of these functions can be accomplished by operating with paper-based tables, the complexity of use is an issue.

4) Interactive entertainment

Some uses had no purpose but pure entertainment (though I usually turned to the newspaper first for entertainment). The PDA allows for many choices in terms of interactive entertainment (the only entertainment program I used was a “vintage” interactive fiction game I remember playing on an Apple IIe as a child). This offers great advantages over paper, where interactivity is impossible (or at least very limited).

How can this use be applied to the world of PDA manufacturers? An assumption being made here is that PDA manufacturers want PDAs to be used more, with the logic being that increased use will lead to increased sales. I have gone from a non-consumer of PDAs to a consumer of PDAs because I cannot imagine myself getting rid of the item in my life–as long as I have the choice to carry it, I will. It truly is valuable to everyday life. Isn’t it a luxury? Yes. But given the choice, I will make sacrifices to carry a PDA. That, and I associate my mindset to incorporate the item–much like I could live without a phone, I will include its use in my foreseeable life. Many other users have not made this transition when it comes to PDAs–they find them to be of little value and though they may have owned one once, they are not in the market for a new one. If the PDA could have been made a valuable part of their lives, they would have continued to use and buy them.

Making an item so valuable to to one’s life as to be almost indispensable is not a new concept. Many people (myself included) have elected to marry themselves to other conveniences–for instance we consider cars to be nearly indispensable transportation tools (most people have plans to always own one) and mobile phones to be almost indispensable communication tools (most people make sacrifices to always carry one). Along these same lines, I have also chosen to marry myself to my Swiss Army Knife (I am using this term generically–I actually own a Leatherman Micra) because it has valuable physical advantages. I use it enough to personally justify carrying it everywhere. [In addition to utility, a host of physical (size and weight), financial (cost), and social (style and legality) factors influence whether a person consider an item to be worthwhile enough to carry on his body.]

The PDA as a mentally valuable item. Many people carry a Swiss Army Knife because it has a lot of physical uses, but virtually nobody carries the individual component devices of a Swiss Army Knife because they would have a limited scope of uses. The PDA has to be a mental Swiss Army Knife before people will carry it. Although PDAs have a few “killer apps” included by default, PDA software has to be heavily modified to enable other uses. Why do PDA manufacturers only include one or two mental tools in their products? This is the equivalent of Victorinox including a great blade on its Swiss Army Knives but then leaving metal stubs for users to change into whatever else they might want–“simply file the stub into a bottleopener, screwdriver, or file”! Of course, most people would not buy the knife in the first place and only a small percentage of purchasers would actually invest the time to make the modifications. Thus, the knife would sit on the shelf for a great majority of purchasers. By not being carried, the utility of the knife is nil. It is only when people start carrying the knife that it will become a truly indispensable item. There are two principles in play here:

1. Realizable (not potential) utility creates use. Swiss Army Knifes are most likely to be useful when they present the greatest chance of everyday use. Thus, Swiss Army Knives include most tools that are “everyday useful.” This sounds stupidly simple, but it requires a focus on utility that Victorinox has but PDA manufacturers do not. PDAs only have the potential to present great everyday utility, and thus are only potentially very useful. Currently, the potential is only met by users investing resources into including the mental tools (i.e. programs) that they consider useful to their lives. If the PDA reaches a threshold where it is “useful enough to always carry” then the individual user will reach the second principle, that of making the item available at all times. Of course, there are some consumers for whom the usefulness of the default programs alone is considerable, and they don’t modify the software. I can only imagine that this group would grow if the default program base grew as well.

2. Realized utility will cycle into more use as the user considers the PDA to be mentally valuable. PDAs have to be made useful enough to warrant being carried in all situations. Who would want to carry a tool in all situations unless that tool can be used in all situations? This is why most electronic items are not touched until the user anticipates a specific use. PDAs are only truly powerful when they reverse this trend–that is, when they are carried universally–even before the user has a specific use in mind.

What is the take-home message from this case study interpretation? The case study data show that PDA use can offer a diversity of mental advantages to users. By fulfilling the category needs that are outlined above (by installing software), users can find their PDAs to be more useful than they currently do. If individual users find PDAs extremely useful, they will begin to consider them to be indispensably-valuable mental tools. Thus, an effective step that PDA manufacturers can take to reach new users and retain old users is to consider ways they can expose customers to the mental advantages that PDAs offer. This is likely to mean that manufacturers should include (by default) software that allows users to do this.

Problems in implementing this interpretation. One assumption that has been made throughout the above argument is that useful software could be made available to PDA users. Obviously, if programs are very difficult for most consumers to use then then they would not make PDAs more useful–in fact, they could make the device more frustrating and video porno italiani less appealing. PDAs offer a unique interface when compared to most other computing devices, so the process of creating useful software may require a substantial investment into researching the user experience.

Notes on the personal side of PDA use

Up to this point, I have written about the behavior that I engaged in with a PDA–the numbers and reasons. Another important aspect about PDA use is emotional in nature. I use my PDA no fewer than 5 times a day, and I consider the useful of its data to have been life-changing.

It feels good to know. People need references when they are in the everyday world. I often like to read at coffeeshops. When I would read a word I did not know the definition for, I would consider the work I would have to put in to get the definition (write it down, look it up when I get home) to not be worth the trouble, especially considering that the utility of the definition was small (I had already read past that point in the book by the time I left the coffeeshop). However, the work it takes to look up a definition in the PDA is minimal (it is always faster than a paper-based reference for me) and the results are immediate. Thus, the number of words I look up has increased substantially when I compare my life to the time when I had to rely on paper-based references.

The PDA is never nagged. Social requests for information are bound by social etiquette. No one likes being asked for boring information or being asked many times. In contrast, the PDA is not inconvenienced when I ask it for boring information–even if I have to ask for a third time. PDAs are uniquely able to fill this social role because of speed-of-use and because it is present in social situations.

The joy of geekdom. Yes, there is an emotional satisfaction that one gets using a PDA to uncover an obscure bit of information. It is not quite the same as the satisfaction that one gets from recalling information mentally, but it is satisfying nonetheless. A friend of mine has a similar PDA and similar programs. When situations arise socially where we need information, we see whose system is best able to produce the useful information. It is usually through these situations that we come to know about new programs and share them with each other. PDAs certainly have social characteristics.

My mindset changed over time of ownership. The questions I asked about the PDA took this course:

What can it do? (Then I discovered useful programs.)

What do I want it to do? (Then I got experience using in everyday life.)

What can it assist me with?

These questions apply well to PDAs because PDAs have changeable software tools. However, my mindset has also changed over the time of owning a Swiss Army Knife. It has certain things it can do (prescribed functions), which perhaps can be changed to become what I want it to do (e.g. the leather punch makes a great mini-screwdriver), but (eventually) it just assists. Obviously, a knife is less flexible than a PDA, but the logic still applies to some degree.

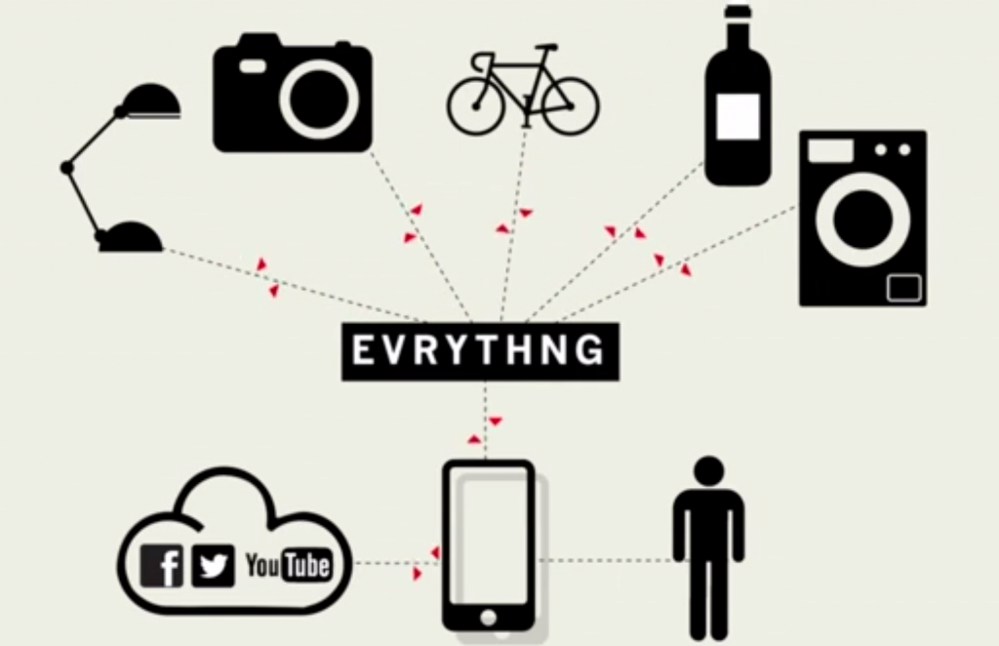

The PDA is a powerful form of distributed cognition. Popular culture has been influenced by a school of thought that tries to address a physical merger of the human body with technology. This school of thought has produced images of artificial electronic limbs, computing devices implanted into the brain, and the like. To apply the philosophy I write about in Brain Machine Interfaces, the human system is able to accept a variety of these devices right now. The only “letdown” is that instead of having artificial limbs and computers internally integrated with the human body, these items have to be made available externally. In other words, a Swiss Army Knife has to be held in the hand and not become part of the physical hand. Likewise, that also means that the mentally-assisting device has to be made available in the form of a handheld PDA. My personal conceptualization of distributed thinking involves a gray line between the internal and external mental systems anyway–so the future is now. The two main areas for the future are device improvements (networking, hardware, and software) and interface improvements (wearability, viewability, and input).