Abstract

The Xist long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) is essential for X-chromosome inactivation (XCI), the process by which mammals compensate for unequal numbers of sex chromosomes1,2,3. During XCI, Xist coats the future inactive X chromosome (Xi)4 and recruits Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to the X-inactivation centre (Xic)5. How Xist spreads silencing on a 150-megabases scale is unclear. Here we generate high-resolution maps of Xist binding on the X chromosome across a developmental time course using CHART-seq. In female cells undergoing XCI de novo, Xist follows a two-step mechanism, initially targeting gene-rich islands before spreading to intervening gene-poor domains. Xist is depleted from genes that escape XCI but may concentrate near escapee boundaries. Xist binding is linearly proportional to PRC2 density and H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3), indicating co-migration of Xist and PRC2. Interestingly, when Xist is acutely stripped off from the Xi in post-XCI cells, Xist recovers quickly within both gene-rich and gene-poor domains on a timescale of hours instead of days, indicating a previously primed Xi chromatin state. We conclude that Xist spreading takes distinct stage-specific forms. During initial establishment, Xist follows a two-step mechanism, but during maintenance, Xist spreads rapidly to both gene-rich and gene-poor regions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscription info for Japanese customers

We have a dedicated website for our Japanese customers. Please go to natureasia.com to subscribe to this journal.

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Disteche, C. M. Dosage compensation of the sex chromosomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 46, 537–560 (2012)

Wutz, A. Gene silencing in X-chromosome inactivation: advances in understanding facultative heterochromatin formation. Nature Rev. Genet. 12, 542–553 (2011)

Lee, J. T. Epigenetic regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Science 338, 1435–1439 (2012)

Clemson, C. M., McNeil, J. A., Willard, H. F. & Lawrence, J. B. XIST RNA paints the inactive X chromosome at interphase: evidence for a novel RNA involved in nuclear/chromosome structure. J. Cell Biol. 132, 259–275 (1996)

Zhao, J., Sun, B. K., Erwin, J. A., Song, J. J. & Lee, J. T. Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome. Science 322, 750–756 (2008)

Pontier, D. B. & Gribnau, J. Xist regulation and function eXplored. Hum. Genet. 130, 223–236 (2011)

Brown, C. J. et al. The human XIST gene: analysis of a 17 kb inactive X-specific RNA that contains conserved repeats and is highly localized within the nucleus. Cell 71, 527–542 (1992)

Jeon, Y. & Lee, J. T. YY1 tethers Xist RNA to the inactive X nucleation center. Cell 146, 119–133 (2011)

Pinter, S. F. et al. Spreading of X chromosome inactivation via a hierarchy of defined Polycomb stations. Genome Res. 22, 1864–1876 (2012)

Simon, M. D. et al. The genomic binding sites of a noncoding RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20497–20502 (2011)

Brockdorff, N. et al. The product of the mouse Xist gene is a 15 kb inactive X-specific transcript containing no conserved ORF and located in the nucleus. Cell 71, 515–526 (1992)

Wutz, A., Rasmussen, T. P. & Jaenisch, R. Chromosomal silencing and localization are mediated by different domains of Xist RNA. Nature Genet. 30, 167–174 (2002)

Sarma, K., Levasseur, P., Aristarkhov, A. & Lee, J. T. Locked nucleic acids reveal sequence requirements and kinetics of Xist RNA localization to the X chromosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 22196–22201 (2010)

Ogawa, Y., Sun, B. K. & Lee, J. T. Intersection of the RNA interference and X-inactivation pathways. Science 320, 1336–1341 (2008)

Berletch, J. B., Yang, F., Xu, J., Carrel, L. & Disteche, C. M. Genes that escape from X inactivation. Hum. Genet. 130, 237–245 (2011)

Carrel, L. & Willard, H. F. X-inactivation profile reveals extensive variability in X-linked gene expression in females. Nature 434, 400–404 (2005)

Splinter, E. et al. The inactive X chromosome adopts a unique three-dimensional conformation that is dependent on Xist RNA. Genes Dev. 25, 1371–1383 (2011)

Dixon, J. R. et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485, 376–380 (2012)

Chadwick, B. P. & Willard, H. F. Multiple spatially distinct types of facultative heterochromatin on the human inactive X chromosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 17450–17455 (2004)

Chadwick, B. P. & Willard, H. F. Chromatin of the Barr body: histone and non-histone proteins associated with or excluded from the inactive X chromosome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 2167–2178 (2003)

Marks, H. et al. High-resolution analysis of epigenetic changes associated with X inactivation. Genome Res. 19, 1361–1373 (2009)

Calabrese, J. M. et al. Site-specific silencing of regulatory elements as a mechanism of X inactivation. Cell 151, 951–963 (2012)

Bickmore, W. A. & van Steensel, B. Genome architecture: domain organization of interphase chromosomes. Cell 152, 1270–1284 (2013)

Duthie, S. M. et al. Xist RNA exhibits a banded localization on the inactive X chromosome and is excluded from autosomal material in cis . Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 195–204 (1999)

Lyon, M. F. The Lyon and the LINE hypothesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 14, 313–318 (2003)

Kohlmaier, A. et al. A chromosomal memory triggered by Xist regulates histone methylation in X inactivation. PLoS Biol. 2, e171 (2004)

Yildirim, E. et al. Xist RNA is a potent suppressor of hematologic cancer in mice. Cell 152, 727–742 (2013)

Engreitz, J. M. et al. The Xist lncRNA exploits three-dimensional genome architecture to spread across the X chromosome. Science 341, 1237973 (2013)

Kharchenko, P. V., Tolstorukov, M. Y. & Park, P. J. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nature Biotechnol. 26, 1351–1359 (2008)

Wernersson, R. & Nielsen, H. B. OligoWiz 2.0–integrating sequence feature annotation into the design of microarray probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W611–W615 (2005)

Flickinger, J. L., Gebeyehu, G., Buchman, G., Haces, A. & Rashtchian, A. Differential incorporation of biotinylated nucleotides by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 2382 (1992)

Yildirim, E., Sadreyev, R. I., Pinter, S. F. & Lee, J. T. X-chromosome hyperactivation in mammals via nonlinear relationships between chromatin states and transcription. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 56–61 (2012)

Bowman, S. K. et al. Multiplexed Illumina sequencing libraries from picogram quantities of DNA. BMC Genomics 14, 466 (2013)

Keane, T. M. et al. Mouse genomic variation and its effect on phenotypes and gene regulation. Nature 477, 289–294 (2011)

Thorvaldsdottir, H., Robinson, J. T. & Mesirov, J. P. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 14, 178–192 (2013)

Kuhn, R. M. et al. The UCSC genome browser database: update 2007. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D668–D673 (2007)

Huang, W. et al. Efficiently identifying genome-wide changes with next-generation sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e130 (2011)

Ji, X., Li, W., Song, J., Wei, L. & Liu, X. S. CEAS: cis-regulatory element annotation system. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W551–W554 (2006)

Davydov, E. V. et al. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++. PLOS Comput. Biol. 6, e1001025 (2010)

John, S. et al. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nature Genet. 43, 264–268 (2011)

Hiratani, I. et al. Global reorganization of replication domains during embryonic stem cell differentiation. PLoS Biol. 6, e245 (2008)

Peric-Hupkes, D. et al. Molecular maps of the reorganization of genome-nuclear lamina interactions during differentiation. Mol. Cell 38, 603–613 (2010)

Kim, D. et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36 (2013)

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Overton, I. Tikhonova and A. Lopez, and the MGH Bioinformatics Core. We also acknowledge funding from Yale University start-up funds to M.D.S., the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to S.F.P. and V.K.M., the MGH Fund for Medical Discovery to S.F.P., and the National Institutes of Health (grant F32-GM090765 to K.S., RO1-GM043901 to R.E.K., and RO1-GM090278 to J.T.L.). J.T.L. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.E.K., J.T.L., M.D.S. and S.F.P. designed the experiments; S.F.P., K.S. and R.F. performed cell culture; R.F. and M.D.S. established CHART conditions and performed CHART; S.K.B. prepared CHART-seq libraries; K.S. performed LNA knockoffs; S.F.P. and V.K.M. performed RNA-seq; S.F.P. performed bioinformatic analyses with M.D.S., M.R.-S., R.F. and B.A.K.; M.D.S., S.F.P., R.F., J.T.L. and R.E.K. interpreted the results; J.T.L, M.D.S, R.E.K, S.F.P. and R.F. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Figure 1 Mapping genome-wide distribution of Xist RNA at different stages of XCI using CHART-seq.

a, Experimental scheme for allele-specific analysis of Xist localization by CHART-seq. CO and C-Oligo, capture oligonucleotide; SAV, streptavidin; cas, CAST/EiJ; mus, 129S1/SvJm; comp, composite tracks. b, Carets above Xist schematic indicate target sites of the capture oligonucleotides (labelled 1–9, A, C; see Extended Data Table 1 for sequences). Letters below indicate the location of repeat sequences. XCI activity defined previously12. c, Sites available for capture-oligonucleotide hybridization were determined by RNase H mapping candidate regions of Xist RNA. The RNase H sensitivity of Xist RNA in the presence of various short DNA oligonucleotides (see Extended Data Table 1) was measured by qRT–PCR, compared to a no-oligonucleotide control and to other amplicons of Xist that are not expected to be affected by cleavage. Primers Xp1–6 are defined in Extended Data Table 2. Regions Xp1 and Xp6 demonstrated minimal sensitivity, but regions Xp2, Xp3 and Xp4 demonstrated broad sensitivity and were used to design capture oligonucleotides for CHART. d, Scheme for time-course allele-specific analysis in genetically marked cell lines. Approximate fractions of Xi-positive cells defined by Xist RNA-FISH or H3K27me3 staining9.

Extended Data Figure 2 Validation and analysis of Xist CHART-seq enrichment.

a, The genome-wide density of seven input-normalized CHART-seq data sets used in this study based on comp reads. b, Allele-specific enrichment on each chromosome based on raw aligned reads relative to input (MEF). c, Allele-specific enrichment of control Xist CHART-seq experiments in MEF, including SO (sense oligonucleotide control) and CO40 (CHART-seq performed with alternate mix of 40 capture oligonucleotides, see Methods and Extended Data Table 1), both presented in comparison to CO11 (Extended Data Table 1, capture oligonucleotides used throughout study). Data shown for the X chromosome and a representative autosome (chromosome 13). d, Linear correlation analyses of Xist CHART-seq data sets, including LNA-treated samples, using the comp track showing high reproducibility. Pearson’s r correlation coefficient indicated. Replicates were either biological (d0; d7; MEF) or based on replicate CHART experiments (ES d3; LNA-4978 3 h; LNA-4978 8 h; LNA-C1 3 h). e, Two independent sub-mixtures of capture-oligonucleotides confirm Xist CHART-seq enrichment patterns by qPCR from an independent Xist CHART experiment in MEF cells. Sub-mixture 1 is composed of capture-oligonucleotides X.1, X.3, X.5, X.7, X.9, X.A; sub-mixture 2 is composed of capture-oligonucleotides X.2, X.4, X.6, X.8, X.C (for primer locations see Extended Data Fig. 4 and Extended Data Table 2). f, Allele-specific analysis of d0, d3, d7 and MEF similar to that presented in Fig. 2a. g, Allelic breakdown of enriched Xist segments with grey (n/d, not determined due to lack of SNPs), light blue and red (leaning towards Xa or Xi, respectively), and dark colours for significantly skewed towards Xa (blue) or Xi (red), as defined by cumulative binomial probability (P < 0.05) after normal approximation from effective fragments. h, The locations of the enriched regions compared to the mouse genome (mm9) and the overlap determined for various genomic features. Below, table summarizing peak numbers and chromosomal origin and coverage (in bp, or per cent chromosome length).

Extended Data Figure 3 Correlation analyses of CHART-seq data sets.

a, Scatter plots (below diagonal) of 40 kb-binned Xist CHART-seq comp signals across all pair-wise comparisons. Pearson’s r correlation coefficients are shown in corresponding squares above the diagonal. b, Overview of Xist spreading during XCI. Comp tracks of Xist CHART-seq signals of d7 and d10 replicates (blue), MEF (black). c, Box plot of normalized Xist densities (40-kb bins) at early and late domains. Data were processed as in Fig. 3g and Extended Data Fig. 7c. Normalized median values for each sample are indicated above box. **P < 10−4; ***P < 10−6, one-side Wilcoxon test. The median Xist densities in late domains relative to early domains increase moderately from d7 to d10.

Extended Data Figure 4 The gene bodies of escapees are depleted of Xist, but are often near peaks of Xist enrichment.

a–c, Xist distribution at Kdm5c, Ddx3x and Eif2s3x genes that escape X inactivation in MEF. cas (Xa), mus (Xi) and comp tracks of Xist and comp track of H3K27me3 ChIP-seq are shown. d, qPCR validation of Xist enrichment. All primer sequences are listed in Extended Data Table 2 and the locations of qPCR amplicons are indicated in a–c. pro, promoter; coding, coding region; cas, cas (Xa)-specific; mus, mus (Xi)-specific. Allele-specific qPCR results shown in red/blue (mus/cas). Autosomal active and inactive genes were used as negative controls (Actb, Scn2a1, U2). Yields determined relative to input DNA. Consistent with CHART-seq results, promoter regions of Kdm5c and Ddx3x showed higher Xist signal than corresponding coding regions. Xi-specific enrichment of Xist was only observed at the 3′ region of Eif2s3x, but not at the coding region of Kdm5c. e, Metagene analysis of Xist density across XCI-repressed and escapee genes. Normalized composite density from Xist CHART using post-XCI (MEF) cells was smoothed (2,000-bp windows, sampled every 50 bp using SPP software29) and averaged across genes on the X that are either repressed (black, defined by those that are active on the Xa but not on the Xi in MEF cells) or escape XCI (red, excluding escapee genes at the Xic). Repressed and escapee genes were determined previously9. Profiles calculated using the CEAS software38 package with default settings.

Extended Data Figure 5 Xi-wide gene repression patterns in d7 and MEF cells, and the relationship of Xist establishment domains with various chromatin features of the X-chromosome.

a, RNA-seq reads aligned allele-specifically were tabulated over gene bodies of RefSeq genes (indicated below in grey). Skew in allele-specific reads (mus-cas/mus+cas) is plotted on a range of −1 (expression fully cas-linked) to +1 (expression fully mus-linked). Bar chart shows allelic skew (red >0, blue <0) values over gene bodies for all genes that were significantly skewed (cumulative binomial probability). Grey lines indicate midpoint (skew = 0) for balanced expression between alleles, and −0.5, signifying threefold depletion of the mus-allele and amounting to 67% inactivation. Two replicates each are shown for d7 and MEFs. Analysis here is similar to Fig. 1c. b, Chromosomal organization directs Xist enrichment. Correlation matrix at 200-kb resolution, featuring significantly enriched Xist segments across XCI time course (d0, d3, d7 and MEF Xist), major repeat classes (SINEs, LINEs, LTRs, simple repeats), active and inactive genes (based on calls in d7 cells), strong and moderate EZH2 binding sites, CpG islands, CG%, conservation (GERP), DNase hypersensitivity (DNase HS), early replication timing (in male (1) and female (2) MEF and male d0 cells), Lamin B1 association (in male ES d0 and MEF), and HiC interaction frequencies in male d0 with the Xist locus (Xic HiC) using two restriction digests (HindIII, NcoI). Colours for positive (magenta) and negative (blue) correspond to Pearson’s r values. See Methods for references to source data. c, Repetitive sequences including LINEs, SINEs and simple repeats are not significantly enriched or depleted from d7 Xist CHART DNA compared to input. Repetitively aligning reads excluded from the other analyses were re-aligned to the entire library of known repeat elements in the mouse genome (http://www.girinst.org/repbase/). Hits in Xist CHART in d7 cells were compared to their corresponding input samples. All repeat types (grey), LINEs (pink), SINEs (green) and simple (blue) repeats are shown. Dashed lines represent twofold enrichment or depletion. The results show no enrichment of LINEs in repetitively aligning reads in the Xist CHART relative to input.

Extended Data Figure 6 Xist binding correlates with previously identified moderate EZH2 sites.

a, Normalized read densities of Xist, EZH2 and H3K27me3 on chromosome 13 in d7 cells shown as in Fig. 2a. b, c, Overview of the correlation of Xist RNA with PRC2 and H3K27me3 on the X chromosome and chromosome 13 in d0 (b) and MEF (c). Xa and Xi allele specific and composite (comp) tracks for Xist, EZH2 and H3K27me3 are displayed as in Fig. 2a. d, Strong EZH2 sites have above average ChIP-seq density compared to the broad EZH2 signals on the X in d7. Comp tracks are shown. Many of the strong EZH2 sites are present before XCI in d0 cells, therefore PRC2 can bind these sites independently of Xist9. e–g, Meta-site analysis of the average EZH2, H3K27me3 and Xist signals around strong EZH2 sites identified in d7 (ref 9). The strong enrichment of H3K27me3 signals at strong EZH2 sites are in agreement with the strong correlation of EZH2 and H3K27me3. h, The density plot of moderate EZH2 enrichment sites (blue) is consistent with the broad distribution of EZH2 on the X, and correlates with Xist in d7. Comp tracks are shown.

Extended Data Figure 7 An independent LNA confirmed the chromosome-wide re-spreading of Xist.

a, Overview and zoom-in (bottom) of differential Xist density in MEF cells subjected to LNA-C1 treatment. Comp tracks of Xist CHART-seq signals on the chromosome X of indicated cells are shown in black. Differential regions showing >tenfold enrichment are displayed in purple or grey as in Fig. 3c, d. b, Genomic distribution of normalized Xist CHART densities in comparison with a maximum likelihood enrichment estimate of LNA-C1 8 h over LNA-C1 1 h CHART-seq signals (LNA-C1 8 h > 1 h, green), showing broad, chromosome-wide recovery of Xist on the X in comparison to an autosomal control. c, Significant increase of Xist density within late regions was observed in MEFs recovering from LNA treatment. Top, Xist density changes during XCI establishment in ES cells and in MEFs before and after LNA treatment. Boxplots of 40-kb-binned Xist CHART-seq signals of early and late domains. During ES differentiation, increased Xist density was observed within early domains where genes are enriched, but remained at low levels in late domains where gene densities are low. After LNA treatment, MEFs showed reduced Xist signals within both domains, indicating global loss of Xist coverage and partial recovery at later time points on chromosome X (LNA-4978 8 h and LNA-C1 3 h and 8 h, compared to LNA-4978 1 h and LNA-C1 1 h, respectively). Bottom, Xist recovery in indicated samples, with 40-kb-binned Xist densities normalized to median levels of early domains of each sample to determine how early and late domains recover from LNA knockoff as compared to levels found during de novo XCI. Normalized median values for each sample indicated above box. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0001, one-sided Wilcoxon test. Two independent LNAs consistently showed significant Xist recovery in late domains within hours post LNA treatment. d, Pattern of Xist recovery after LNA treatment with LNA-4978 and LNA-C1. Xist enriched segments (segs) in MEFs (grey, 16,760 total) were split into those common to both MEF and d7 cells (dark grey, 8,910 total) and those specific to MEFs (white, 7,850 total). Changes in Xist density over these sites are shown for d3 − d0, d7 − d0, MEF − d7 and LNA samples (LNA-4978: 3 h stripped, 8 h recovery; LNA-C1 1 h stripped, 3 h, 8 h, 24 h recovery). Replicates indicated with #1/#2. Numerical fold-difference in median of changing Xist density between MEF-specific segs and common-segs indicated above box-plots. After LNA treatment, recovery of Xist density over MEF-specific enriched segs is close to that of common segs (only 1.2–1.3× lower), whereas during XCI establishment Xist increase over these sites is 3.4× and 2.3× higher in d3 − d0 and d7 − d0, respectively. These values are highly reproducible between replicates. Width of notched box plots scaled to square root of total number of enriched segs in each group. Error bars indicate 1.5× interquartile range without extending beyond min/max data points.

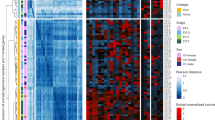

Extended Data Figure 8 Comparison of Xist distribution post-LNA treatment with establishment and maintenance stages of XCI.

a–d, 40-kb-binned Xist CHART-seq data from comp tracks are plotted on a log2 scale. Bins with tenfold enrichment or depletion (median corrected) of one sample versus another are coloured in purple and green, respectively. These regions of difference between samples were mapped along the X chromosome by plotting the CHART-seq signal of the enriched sample. Complete CHART-seq tracks are shown in black. Comparisons are centred on maintenance (a), de novo establishment (b) and recovery from LNA treatment in post-XCI cells, with knockoffs using two independent LNAs showing similar results (c, d).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Simon, M., Pinter, S., Fang, R. et al. High-resolution Xist binding maps reveal two-step spreading during X-chromosome inactivation. Nature 504, 465–469 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12719

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12719

This article is cited by

-

Regulatory mechanism of LncRNAs in gonadal differentiation of hermaphroditic fish, Monopterus albus

Biology of Sex Differences (2023)

-

Gene regulation in time and space during X-chromosome inactivation

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2022)

-

Xist spatially amplifies SHARP/SPEN recruitment to balance chromosome-wide silencing and specificity to the X chromosome

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2022)

-

Non-random chromosome segregation and chromosome eliminations in the fly Bradysia (Sciara)

Chromosome Research (2022)

-

The landscape of lncRNAs in Cydia pomonella provides insights into their signatures and potential roles in transcriptional regulation

BMC Genomics (2021)